Simply put, dental radiometers are a tool clinicians use to measure the light output of curing lights. Although less accurate than sophisticated lab equipment that can pinpoint light output precisely, the portability and affordability of dental radiometers often make them a handy tool for dentists. However, because of their inaccuracy, dentists should use caution when using a radiometer to compare curing lights’ performance, as the radiometer can mislead the doctor into purchasing or using an inferior light—possibly leading to inadequate curing and failed future restorations.

The inaccuracy of radiometers lies in two factors. The first is that a typical radiometer only tests a small portion of the curing light’s output and then uses that sample to predict the light’s overall irradiance. Because most curing lights’ output is non-uniform, the value of light intensity can vary significantly across regions of the light’s tip. Thus, the reading from the radiometer could vary widely from the same light, depending on which portion of the output it tests.

The second reason radiometers tend to give undependable readings is that many radiometers are less sensitive to some light wavelengths than others. This presents an obstacle in getting an accurate reading because most curing lights deliver a broad spectrum of light, impossible for the radiometer to measure properly. This is particularly true when it comes to measuring light output from plasma and broadband LED curing lights.

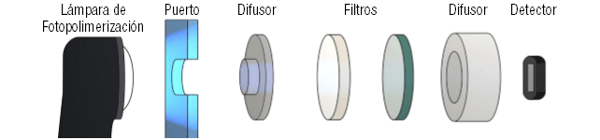

Let’s take an in-depth look at the different parts of a typical radiometer to more fully understand its capabilities. A radiometer consists of these main components: a case, diffusers, filters, a detector, and a display.

Various Parts that Make Up a Radiometer

Various Parts that Make Up a Radiometer

Display

Dental Radiometer with a Digital Display

Dental Radiometer with a Digital Display

Many dentists unwittingly believe their radiometers, especially if digital, give them accurate readings because the display will show an extremely precise reading, such as 927 mW/cm2. However, this number can often be up to ±20% from the actual correct value of the light when measured by even the highest performing radiometers.

Port

Light enters the radiometer through its port. The size and shape of the port present the first restriction to how much light actually reaches the detector. In fact, if you move the tip of a curing light over the port of a typical radiometer, you can observe a wide fluctuation in the irradiance values the radiometer reports. For the radiometer to provide an accurate reading of a curing light’s irradiance output, the light would have to be uniform, which just isn’t the case with most modern curing lights, as they are designed to emit multiple wavelengths to allow them to cure fully polymerize a wide array of dental materials—from porcelain to composite to resin cements.

For example, if a curing light has an irradiance hotspot that the radiometer picks up, the radiometer will erroneously calculate a much higher irradiance value, misleading the clinician to believing the light is much stronger and more powerful than it is, and vice-versa.

Radiometer Port Measuring Light at Close Distance (0 mm)

Radiometer Port Measuring Light at Close Distance (0 mm)

Additionally, the distance at which a curing light is measured from a radiometer’s port also plays an important role in how accurately the device can measure light output. Measuring a light’s output right at the tip (0 mm distance) is not a valid indicator of the light’s performance in a clinical setting because not only are few composites cured at 0 mm distance, but the irradiance of some lights declines rapidly, even over distances as small as 10 mm.

Diffusers

Since it is known that light entering a radiometer will have areas of high and low intensity, radiometers contain diffusers in an attempt to distribute that light more evenly before it reaches the detector. This is, in theory, supposed to make the portion of light reaching the detector an accurate representation of the light the curing light emits as a whole, but it still does not allow the detectors to measure the various wavelengths of light across the entire curing light’s tip.

Since it is known that light entering a radiometer will have areas of high and low intensity, radiometers contain diffusers in an attempt to distribute that light more evenly before it reaches the detector. This is, in theory, supposed to make the portion of light reaching the detector an accurate representation of the light the curing light emits as a whole, but it still does not allow the detectors to measure the various wavelengths of light across the entire curing light’s tip.

Filters

After traveling through the radiometer’s diffusors, the light may go through several filters, which reduce the intensity of the light at certain wavelengths. The nature and amount of filtering varies between different brands of radiometers. In some cases, the violet light from an LED curing light may be almost entirely filtered out by the radiometer before reaching the detector. Therefore, the light meant to cure some of the alternative photoinitiators used in some resins maybe not be included in the irradiance value reported by the radiometer.

Detector

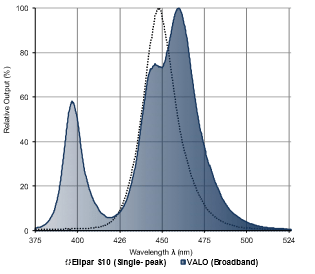

The light being measured from the curing device reaches the end of its journey when it hits the detector, whose sensitivity to different wavelengths is not uniform, which leads to inaccurate measurements. The graph below shows the VALO® curing light’s relative spectral output. For comparison, the dotted line is the output from a common single-peak LED curing light. The area under the VALO® light’s spectrum is shaded heavier or lighter depending on the sensitivity of the detector to light at that wavelength. The lighter the shading, the less sensitive the detector. As you can see by looking at this graph, the broader the spectral range of the curing light, the greater the variation in the detector’s sensitivity. This means that the detector is less sensitive to the total output from broadband lights with violet LEDs than from single-peak LED curing lights such as the Elipar™* S10 curing light. This is because the violet light from is not as detectable by a simple radiometer and thus counts less towards the displayed irradiance value.

Relative output power of Valo (Broad Spectrum) with a shading representing the

sensitivity of BS500A photometer and the relative power of a single peak lamp

When to Use a Radiometer

Despite the known limitations of dental radiometers, they can be useful for clinicians for to monitor any output changes that may occur over time. Most researchers and educators on the subject recommend to check the curing light irradiance periodically with a handheld radiometer and document the results on a spreadsheet.

Even if the actual number may not be accurate, the clinician can tell when there is a significant drop in the output and send it for repair or replace it, minimizing the risk of underpolymerized composite restorations due to a malfunctioning light curing unit.